Goods

Proposal with Kristine Ericson, Alison Kung, and Ashley Takacs for the ‘Shop’ phase of Collage Lab's Post+Capitalist City competition. The brief asked us to re-imagine the shopping experience in a post-capitalist context.

In a typical American grocery store, the diversity of choices within a particular product category may seem absurd and unnecessary. A moderately sized store will display more than twenty types of cranberry juice and fifty brands of breakfast cereal. Loudly colored and diversely shaped packages visually distinguish these products from one another, though their actual contents may be nearly identical.

Many elements of food packages, including slogans, mascots, brand names, and logos, may make certain products seem desirable as objects and not simply as items for consumption. This type of seductive packaging is most common among processed and artificial foods--cereals, sugary drinks, condiments, snack foods, and candy. Meanwhile, the necessary staples of cooking and healthy eating--fruits, vegetables, bread, meat, milk, and cheese--receive little if any packaging. These basic items require minimal labeling to convey their desirability and necessity.

The following proposal addresses a number of questions regarding the relationship between packaging, retail architecture, and product consumption. Capitalist marketing campaigns and branding strategies may convince us that we “need” certain items, but how would shopping habits change if food packages bore no brands or distinctive labels? Would the elimination of varied labels allow consumers to see food products for what they truly contain? If products were not mediated by marketing strategies, would we buy fewer unnecessary things?

Our proposal envisions a corporate entity that exercises total control over the display of products in its grocery stores, enforcing the elimination of existing brand labels and introducing a generic labeling system. Uniformly colored and formatted containers forcibly erase the distinctions between previously branded products and display only the basic facts of an item--its name, nutritional information, and ingredients--the bare information required for consumers to decide if a product is necessary to purchase and consume. Such hegemonic control of the means of packaging and displaying products is not in fact so far removed from the current organization of food distributors in America, as only a handful of large corporations control the major brands found in grocery stores. Thus the overwhelming variety that we experience in grocery stores is largely false, as specialized brands are likely owned by massive conglomerates.

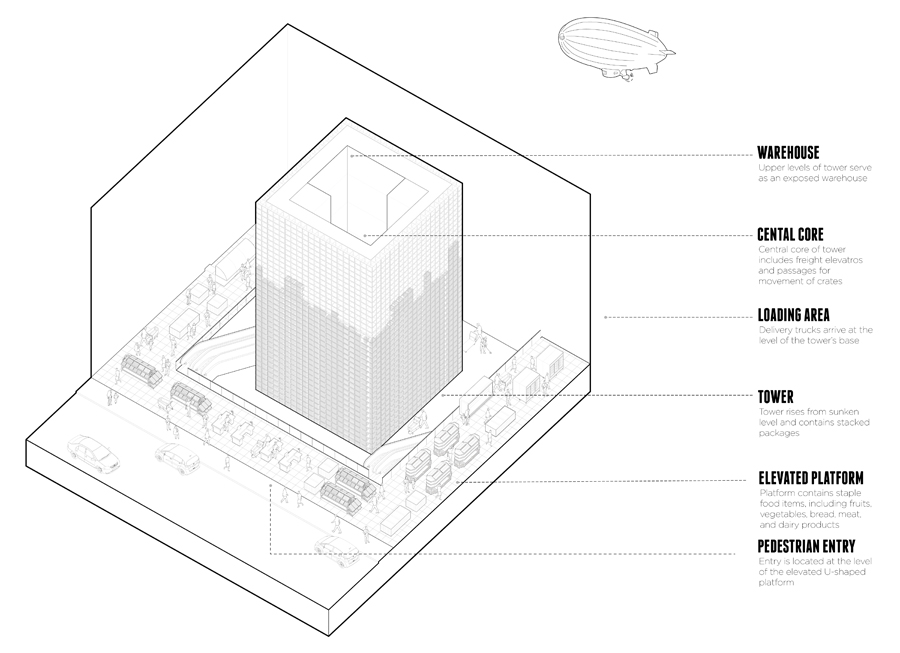

The store’s architecture refers to typical American grocery store configurations, in which the fresh items of produce, meats, baked goods, and dairy products wrap along the perimeter of a store, while non-perishable canned, bottled, and packaged foods fill the remaining interior space. In this proposal, a U-shaped platform serves as the entry to the store, containing the fresh foods that constitute most of the staple elements of a person’s diet, along with essential items such as flour, sugar, and other dry goods.

The interior of the U is sunken below this platform, and from this lower level rises a tower that displays uniformly packaged products. The lowest tier of the tower contains packages within reach of passing customers, while the upper tiers constitute an exposed warehouse.

Displayed along the perimeter faces of the tower, the monochromatic packages visually blend into one another to form a single sculptural mass. Variations in package sizes and geometries generate modulations of light and shadow and a subtle visual texture of positive and negative space. The strict prismatic quality of the tower suggests the artificiality of the processed and preserved foods it contains, while the large mass of the upper warehouse space, normally hidden in stock rooms or off-site storage centers, makes visible the excessiveness of processed grocery items and of the material and labor expended on maintaining the existing grocery store system.

With the stacked products acting as a perforated screen, the warehouse levels offer momentary glimpses of the stocking activities taking place behind. This screen acts similarly to milk and dairy cases in typical grocery stores, which serve as thresholds between the space of the store and the hidden space of the stock room, briefly revealing the usually invisible inner workings of the store’s operation. Thus the tower may be compared to factory and warehouse architecture that puts production and assembly activities on display in order to dramatize these capitalist processes for the consumer, but here the tower emphasizes the excesses of production and large-scale store maintenance.

The packaged products themselves may be seen as building blocks that compose the tower and call attention to the materiality of containers and their often artificial contents. With the space being defined by massive walls of packaging, consumers may be prompted to view these products as substantial objects and potential waste material, which might in turn lead them to become more conscious and wary of the amount of packaged items they buy. By eliminating distinctions between different products, the system visually transforms them into generic “goods” to be accumulated.